Theme 1: Womens Work

How can gender inequality can shine a light on pay inequalities in care? (Part 1)

As part of our #ActForCare campaign we are holding a series of monthly webinars on areas concerning care work. This blog introduces concepts for our first webinar and campaign focus: how care is perceived as ‘Women’s Work’. For more details, please click here to visit our website page dedicated to the campaign. --And click here for our free 'Care as Women's Work' webinar

This two-part series will explore how the low pay of care workers is connected to how women dominate the care workforce and the high representation of non-white persons in the care workforce.

In Part 1 we will explain a feminist theory called intersectionality, coined by Kimberle Crenshaw and how it can be used as a framework to understand the situation of low pay for care workers.

In Part 2 we will apply intersectionality on how care workers labour is valued via historical narratives around care work with looking at gender and race.

We will also cover the inequalities surfacing with the COVID-19 pandemic, and how better funding to the sector is a step forward for gender and racial equality!

Introduction

The care workforce is one of the lowest paid in the UK.

The average hourly pay for care workers is currently below the basic pay rate for most UK supermarkets (Kings Fund, 2019).

A worker with more than 20 years’ experience in the sector will only see their pay rise by £0.15 an hour (Kings Fund, 2019). It is no secret that the care sector has been relentlessly underfunded for a decade, and COVID-19 has further highlighted the essential role care workers play for severely poor wages.

Perceptions and pay

We submitted evidence of a survey completed by 400 care workers to the Health and Social Care Committee inquiry into ‘Social care: funding and workforce’.

Our submission captured four themes from the responses, with the first theme as Pay, Funding and Rewards. We found that levels of pay and how it is distributed through pay scales would show value and recognition for the skills, pressure and compassion of the workforce.

76% of our respondents said that improving pay is the most crucial aspect of improving their working conditions.

To check out more information on our submission, click here

Public perceptions and attitudes surrounding care work is a key foundation to the pay, funding and commissioning of care work.

Care work is painted through media negatively, always largely focusing on the ‘negligence’ and ‘limited skills’ of the workers (Kings Fund, 2019). Largely these workers are women and have a high representation of non-white groups.

Women and women of colour are delivering the majority of our essential care services, looking after the unwell and maintaining the sustainability of our care sector but are earning ‘poverty wages’ (Women’s Budget Group, 2020).

Pay shows a clear message of how workers are valued. Improved pay and funding would show recognition for the care workforce. For too long, the care workforce’s compassionate nature has been taken advantage of and largely overlooked as unskilled, “women’s work”. If not addressed, the quality of care provision will be at a further crisis and continue the injustice of racial and gender equalities.

What is intersectionality?

Intersectionality was coined by feminist academic Kimberle Crenshaw, a leading academic, civil rights advocate and American lawyer. Crenshaw discussed how feminism neglects race and by doing this, discriminates against women of colour.

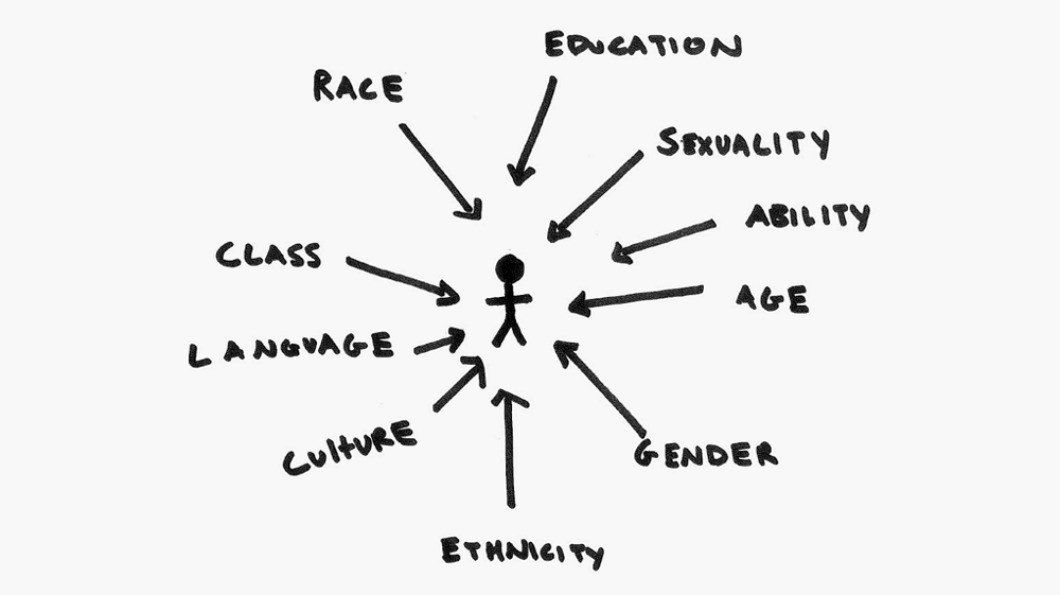

The term is used to show how a woman’s experience is not just defined by her gender but her race, ethnicity, sexuality, ability and more.

It shows that women are affected by multiple forms of marginalization and that white, heterosexual, able-bodied or middle-class ‘social identities’ are favoured in society. It then also describes systems of oppression, such as racism or patriarchy are discriminations against social identities.

This shows that racism would be discrimination of a racial identity, or patriarchy would be a discrimination of gender. This would mean that a black woman, could experience two systems of oppression at once: racism and patriarchy.

This image is a great example of how our identity is made up from many factors.

You can watch Kimberle herself briefly explaining it herself here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ViDtnfQ9FHc

and her explaining the concept in more detail on a TED Talk, if you have more time:

https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality?language=en

How is it useful for care work?

According to the Skills for Care, State of Care report, the current care workforce is said to be made up of 83% female workers in comparison to 52% of the population and 21% BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethic) in comparison to just 3% of the population (Skills for Care, 2019).

Intersectionality is an important tool to use in policy work as it is able to consider that gender or race can be a direct barrier to accessing things like career progression, training and appropriate standards of pay. For example, our pay gap analysis research from Manor Community (click here to visit) found that non-white groups are more likely to stay in entry level positions and see a slower pay rise than white groups. According to the Skills for Care State of Care report, women highly-represent the workforce, but male, white workers are more likely to be in senior positions. (Skills for Care, 2019).

How is gender or race important for understanding how care work is valued?

Intersectionality can help us see how gender and race intersects with racist or patriarchal attitudes of labour. The undervaluing of care work with low pay and funding is connected to cultural attitudes of women and people of colour. We are going to be looking at this in part 2!

How can gender inequality shine a light on pay inequalities in care? (Part 2)

We have looked at pay, and how this is disproportionately impacting women and persons of colour due to the high representation of these groups in the care sector. In this blog we are using intersectionality to go deeper into gendered and racial attitudes of labour.

We will also cover how COVID-19 has highlighted the inequalities of care workers, putting themselves at risk everyday with little to no reward or recognition.

Gender

New paragraph

The first intersection we are looking at is gender and patriarchal attitudes of labour.

How care is perceived is embedded in the history of care and the model of a heterosexual family. In the twentieth century, ‘independent’ men were meant to provide financially (breadwinner) whilst ‘dependent’ women were meant to provide unpaid domestic work and care work. This was even reflected in policy, where care was only provided to families who could not look after those in need (Joya Misra, 2007).

It wasn’t until the 1990’s that the care of children and the elderly for work became a norm. Women were joining the workforce in huge numbers and the start of part-time work began to accommodate for mothers in the workforce. The increasing of women’s employment gave rise to policy to encompass women as independent financially, however the permanence of the man/breadwinner and woman/dependent remains very much ingrained into society.

Women still have more dependents than men and take on more unpaid domestic tasks or care responsibilities at home. Women “carry out at least two and a half times more unpaid household and care work than men” and this “subsidizes the cost of care that sustains families, supports economics and often fills in for the lack of social services” (UN Women, 2016).

The identity of care work is based upon foundations of relationship building, person-centred, compassion and nurture. These attributes have often been assigned to women under the breadwinner model (Pew Research Centre, 2018) (Liz Bondi, 2008). These types of skills are expected to be done for free and there is little appreciation for them as they are perceived as ‘natural’ to women.

This means that the sector is understood as ‘feminine’ making it ‘feminized’. This attitude works under a patriarchal system, which ‘women’s work’ is systematically undervalued and exploited with low wages. This places all people in the sector, men and women, at a severe disadvantage.

Within our recent submission to the Health and Social Care Committee’s inquiry on workforce (click here to visit) we found that care workers feel that the low pay they receive is because of the lack of recognition for the work they do. Our respondents felt that pay reflects how their skills are recognised. Women’s skills in particular are systematically undervalued as occupations dominated by women are paid less.

Race

The second intersection we are going to look at is race and racist perceptions of labour.

Non-white people are expected to carry out labour intensive work with little reward or recognition. Rooted in the era of slavery onto post-slavery and present day, there is embedded ideas in society that people of colour are low-wage domestic or agriculture workers (Nina Banks, 2019).

Deep seated views about the skills and competencies of non-white people is driven from racist stereotypes and attitudes of these workers.

The value of women of colour’s work is heavily tied to their lower privilege in comparison to white women. Dating back to the era of slavery, women of colour faced violence and exploitation for free care labour without having rights to their own children (Jocelyn Fyre, 2019). Black women are undervalued as mothers but are expected to carry out domestic, care-giving jobs associated with motherhood (Jocelyn Fyre, 2020).

Today, women of colour

disproportionately make up the care workforce and face

occupational segregation. This means they are highly concentrated in jobs with low pay, part time and unstable contracts (TUC, 2006).

Women of colour are put at an intersection of gender and race, whilst frequently having to push past negative, outdated stereotypes and beliefs on their work ethic and non-deserving of higher wages. Women of colour face these unique challenges, showing the need for intersectionality to understand the disparities not just between men and women, but women of colour and women.

Combining that care work is often undervalued anyway, that women and non-white persons highly represent the field and that women’s and non-white persons work is systemically undervalued itself, would explain a part of the under-funding of the sector.

COVID-19 and non-white staff

The current pandemic is making clear the current inequalities in the care sector and this burden of care put upon women and non-white people. Those working on the front line of the pandemic are paying the highest price. Pay and funding for care workers is not reflecting this risk with a huge concentration of workers on less than minimum wage (The Resolution Foundation, 2020).

UNISON stated that 72% of health and social care staff who have died from COVID-19 are Black (UNISON, 2020). Black African women in the UK have a mortality rate four times higher than White women (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2018). Due to the high concentration of non-white staff and women in the care workforce, the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) is disproportionately affecting these groups. Care workers are working at close proximity to the virus and not having adequate pay or access to PPE emphasizes it as an inequality issue.

Better pay means equality

A focus on the direct racial and gender biases that impact appropriate pay is vital. It is fundamental for the government to deliver funding for care services and boosting pay to advance the interests of women and non-white persons. By putting forward this action, it will show support to not just stabilizing the care system but a step towards improving inequality. Better pay and funding shows commitment to valuing the care sector and the skills of women and people of colour care workers.

If you are interested in discussing any of these topics mentioned, please come join our free webinar ‘Womens Work’ on August the 14th 12.30-1.30pm.

More details and sign up here:

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/act-for-care-webinar-social-care-and-womens-work-tickets-115035393960

References

Jocelyn Fyre, 2019. Racism and sexism combine to shortchange working black women. Online: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/news/2019/08/22/473775/racism-sexism-combine-shortchange-working-black-women/

Jocelyn Fyre, 2020. On the frontlines at work and at home: the disproportionate economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic on women of colour. Online: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2020/04/23/483846/frontlines-work-home/

Joya Misra, 2007. Earner-Carer Model. Online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeose002

Kings Fund, 2019. Average pay for care workers: is it a supermarket sweep? Online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2019/08/average-pay-for-care-workers

Liz Bondi, 2008. On the relational dynamics of caring: a psychotherapeutic approach to emotional and power dimensions of womens care work. Online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09663690801996262

Nina Banks, 2019. Black women’s labor market history reveals deep-seated race and gener discrimination. Online: https://www.epi.org/blog/black-womens-labor-market-history-reveals-deep-seated-race-and-gender-discrimination/

Pew Research Centre, 2018. Strong men, caring women. How Americans describe what society values (and doesn’t) in each gender. Online: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/interactives/strong-men-caring-women/

Resolution Foundation, 2020. What happens after the clapping finishes? Online: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/what-happens-after-the-clapping-finishes/

Skills For Care, 2019. State of the adult social care sector and workforce in England. Online: https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/State-of-Report-2019.pdf

The Point, 2020. The scandal of low pay in the home care sector. Online: http://www.thepointhowever.org/index.php/issues/207-the-scandal-of-low-pay-in-the-home-care-sector#:~:text=The%20Resolution%20Foundation%20report%2C%20(Under,less%20than%20the%20minimum%20wage.

Time, 2019. What’s intersectionality? Let these scholars explain the theory and its history. Online: https://time.com/5560575/intersectionality-theory/

TUC, 2006. Black women and employment. No 56 in the TUC welfare reform series. Online: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/black-women-and-employment

UN women, 2016. Redistribute unpaid work. Online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/redistribute-unpaid-work

UNISON, 2020. COVID-19: Black and female workers on the frontline. Online: https://www.unison.org.uk/news/article/2020/05/covid-19-black-female-workers-impacted-rest/

Womens Budget Group, 2020. It is women, especially low-paid, BAME & migrant women putting their lives on the line to deliver vital care. Online: https://wbg.org.uk/blog/it-is-women-especially-low-paid-bame-migrant-women-putting-their-lives-on-the-line-to-deliver-vital-care/

Don't forget to check out our Act for Care page - Click HERE to visit.

Privacy | Sitemap | Contact us | Login

CoProduce Care Ltd. All rights reserved.